( Aleteia ) For 1200 years the Roman Forum thrived as the legislative, religious and administrative nerve center of Rome. From the little kingdom founded in 753 BC to the SPQR of the Roman Republic to the mighty Empire, the little open area grew from marketplace to city center to hub of the world. But then what happened? When the Empire fell in 476, did the Forum just cease to be?

No, it did not. Despite the implosion of the Roman government, the Forum continued to develop, transforming as new overlords came to settle on the Palatine Hill. Its survival instinct, however, was no longer fueled by the old pagan gods, but by Christianity. As the temples were gradually abandoned, Christian churches came to redefine the space of the Forum.

These mysterious years, often pejoratively called the Dark Ages for lack of historical record, receive a colorful testimony in an exhibit on display in the Forum until Oct 30, 2016. For those who think they have “done” the Forum, “Santa Maria Antiqua tra Roma e Bisanzio” reveals 300 years of history after the Roman Emperors exited center stage.

The exhibit is housed in the Church of Santa Maria Antiqua, a 7th-century church nestled into the remains of the imperial palace. Covered by a landslide caused by an earthquake in 847, the church was unearthed in 1904 and briefly studied before shutting down for a 40-year restoration that concluded just a few years ago. This exhibition is the first time the general public has set foot in the church for half a century.

Walking toward the church is a like a time warp of history. Passing under the massive platforms of the temples to the many gods of Rome, one steps into the atrium of the church. Colossal walls, the remains of Emperor Domitian’s ambitious palace, dwarf the visitor, and the floor bears the traces of Caligula’s fountain, a remnant of that capricious emperor.

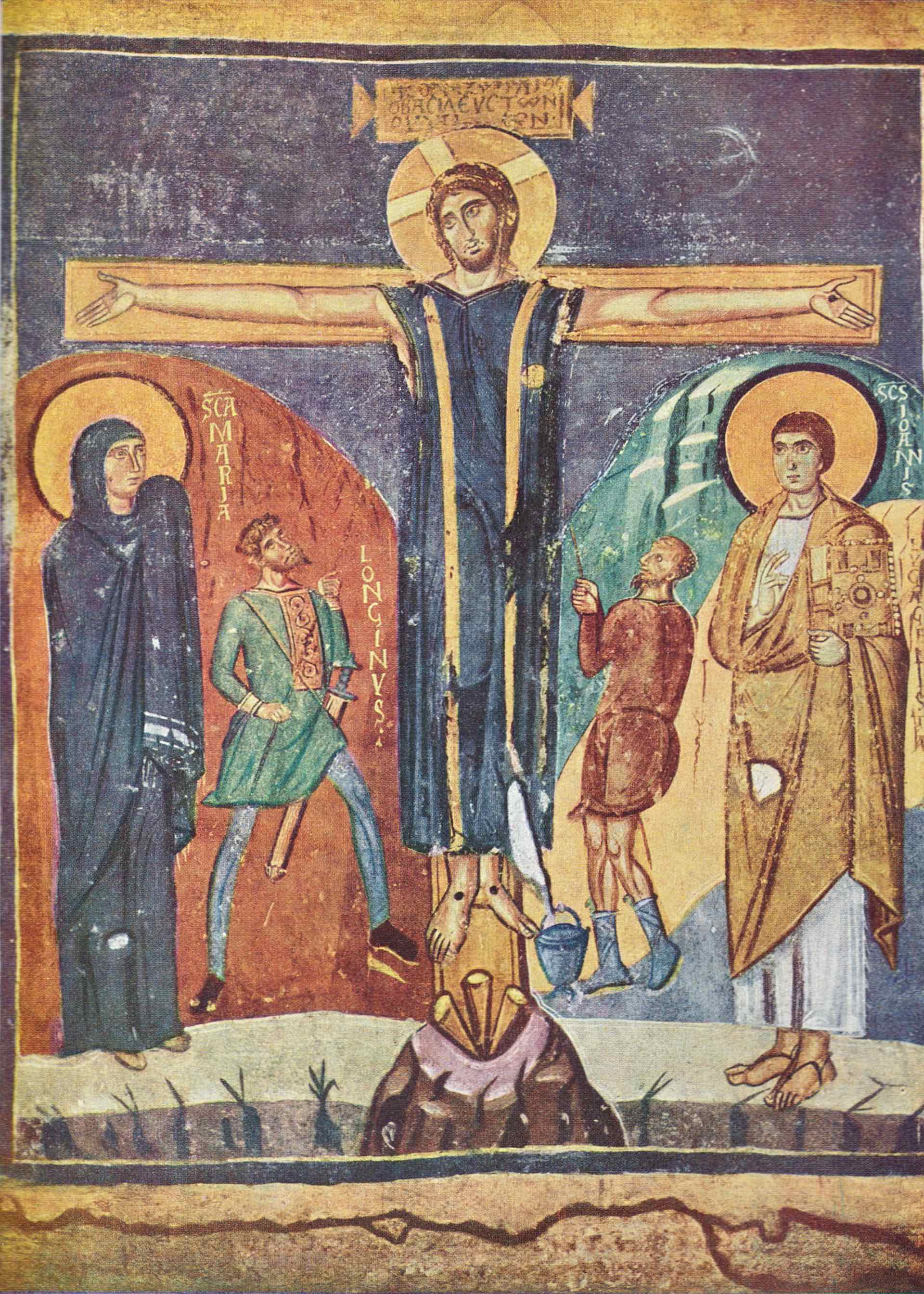

A few fresco fragments clinging to the walls of Domitian’s library hint at what is to come. After the dizzying heights of Imperial architecture, Santa Maria Antiqua seems intimate. This space dazzles in a very different fashion. Every wall, every column, every surface bears traces of fresco – this Fabergé egg of a church is a treasure trove of art recounting the spiritual life of the Forum from the Ostrogoth Kings who wrested Rome away from the Emperors in the fifth century, through the iconoclast controversy, to the age of Charlemagne, which dawned shortly before the church was obliterated by the landslide.

The exhibit follows a carefully constructed itinerary. On entering, visitors stand the nave where several statues stand as sentinels—the new rulers of Rome who allowed Christianity to flourish in the Forum. One striking queen gazes vacantly with inlaid eyes from under her pearl studded crown. She may be Amalasunta, daughter of Theodoric, sponsor of the first Christian church in the Forum: Saints Cosmas and Damian, built in 525.

As if by magic, an arresting icon of the Virgin and Child hangs in midair over the nave. Painted for this church between 575 and 600, it was submerged after the collapse of the church, but salvaged and brought to a new church that became Santa Maria Nova in the temple of Venus and Rome.

The star of the exhibition is Pope John VII, whose brief pontificate from 705 to 707 brought about huge changes in the church. Son of the Byzantine viceroy, John had a foot in both Greek and Latin culture as well as a love of art, and he used this church as a court chapel. His oratory to Mary in St Peter’s Basilica was covered with stunning mosaics–several are in the show despite the destruction of the chapel in the 1500s, along with an engraving with the pope’s signature reading “John, servant of Mary.”

Santa Maria Antiqua contains some of the first side chapels and the oldest extant chapel to be dedicated by a layperson. The first chapel on the right was decorated under Pope John VII and dedicated to medical saints. Crossing the threshold, five healers are painted in a row, holding their medical instruments, including the Eastern martyrs Cosmas and Damian, the doctor twins who were introduced to Rome to ease the cultural tensions of a new Byzantine Emperor and to supplant the memory of Romulus and Remus, the twin founders of the pagan city.

The chapel to the left of the apse is even more striking, built in the mid-8th century by Theodotus, a wealthy court official. Once marble-encrusted, the walls were cleared of some of the stone adornment to make room for a depiction of the brutal passion of Saints Giuditta and Quirico, a mother and son martyred in the East.

These images are very fragmentary, but sophisticated computer graphics fill in the missing sections, astounding viewers with a vision of how the chapel would have appeared in its glory. It is a breathtaking application of technology in art.

The apse area is the stuff that art historians dream of. High on the right side of the apse there is a patchwork of fresco. Pieces have chipped away revealing the several different stages of decoration in the church.

Below you will find a before and after comparison of some of the art inside the church.

Clever illumination helps guide viewers through the eras of the “palimpsest wall.” The oldest fresco, Maria Regina, shows a stiff upright queenly figure with a pearl-encrusted headdress holding a child as an angel bows nearby. The work dates to 550, when Santa Maria Antiqua first discovered its Christian identity as the guardhouse to the Ostrogoth kings.

Between 600 and 649, an elegant Annunciation featuring “the beautiful angel” covered the earlier work. Then John VII added an array of Church Fathers as part of his grand plan for the decoration of the apse. The immense scene features angels, saints and martyrs adoring the cross. A little watercolor nearby shows what it once looked like: an explosion of color to bring triumphant heaven closer to earth.

The church is striking in its antiquity, but also previews some of the more modern splendors of church art. The walls are decorated with false painted draperies, unfurling parallel narratives—Old Testament to the left and the New Testament to the right—and Jonah lounges on a carved marble sarcophagus to the side. This style of decoration survived iconoclasm and artistic fads, and these same components can be found in the Upper Basilica of Assisi or the Sistine Chapel over half a millennium later.

Santa Maria Antiqua amply demonstrates that beauty—ever ancient and ever new—has long been the Church’s business.